By 2025, more than 100 million smartphone users in the US will use a QR code scanner on their mobile devices, compared to 70.6 million in 2020 1. But how can citizens be sure that what they are scanning is legitimate?

The steady growth in the use of smartphones to scan QR codes was accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly because of the necessity to scan health passes.

Other key accelerators will come in a few years’ time. 1D linear barcodes on retail product labels will be replaced with the more data-rich 2D barcodes. And the EU’s EcoDesign for Sustainable Products Regulation will progressively implement digital product passports, in the form of 2D barcodes, across various industries. These accelerators will have the effect of drawing even more smartphone users to deploy their scanners.

Against this backdrop of potentially billions of products carrying QR or other 2D barcodes in the near future, QR code scanning will only continue to grow.

Unfortunately, simply scanning a QR code can lead to a significant risk of substitution fraud. Real-life cases of this type of fraud – known as quishing – include fake COVID certificates and fake QR codes on parking fines and meters.

In one case, fraudsters pasted their own QR code – which connected to a counterfeit website – on top of legitimate codes on parking meter signs, in order to steal people’s payment card details. Drivers unwittingly scanned the fake code, thinking they were paying for their parking online, but were in fact exposing themselves to serious financial loss.

With these dangers in mind, government authorities should be ready to propose secure, interoperable solutions that mitigate the risks arising from fraudulent physical and electronic documents or products.

Today, however, no global approach exists for mitigating the dangers of scanning QR codes – although the framework for such an approach is already in place, in the form of two ISO standards. (As a matter of interest, these standards were written by the same expert working group that created the ISO standard for tax stamps – 22382:2018 – which is currently under revision.)

The first standard – ISO 22385:2023 – consists of guidelines to establish a framework for trust and interoperability. This is related to the use of electronic certificates, such as those securing the microchip data on a credit card or passport.

Then there is ISO 22376:2023, for specifying and using interoperable, visible digital seal data formats for authenticating, verifying, and acquiring data carried by a document or object.

Although QR code reading with a smartphone camera can already be considered a form of interoperability, it is not a secure one. However, these two ISO standards can together provide the basis for a secure solution.

A visible digital seal (VDS) is defined as a standardised, structured dataset containing a payload (the actual data itself) and an electronic signature (or ‘seal’) provided by the issuer of that data. The data and the signature are encoded into a 2D barcode which can be either printed on a document or product, or displayed electronically.

For a travel visa, for example, the payload would include the name, nationality, date of birth, sex and passport number of the visa holder, as well as the visa validity period.

The purpose of an electronic signature is to certify the identity of the issuer and guarantee the integrity of the data. It does this, not by keeping the data secret, but by confirming its authenticity and detecting any modifications that may have been made.

The VDS approach works with a trusted network comprising a trust service operator (TSO), a trust service provider (TSP) and a trusted entry point (TEP).

The TSO is a body responsible for defining a particular global electronic certificate scheme, including how the scheme can be used, who can use it and for what purpose certificates can be created, validated and stored. The various documents falling under such a scheme – which could range from ID cards and residency certificates, to tax stamps and customs documents – serve to define the use cases that will require a VDS.

In France, the French national ID card is part of a VDS scheme under the Otentik Trust Network. The card is issued by the Ministry of the Interior, one of the bodies governing the scheme’s trusted network.

A VDS scheme also needs TSPs. These consist of public and private companies – such as technology providers and banks – which offer certification and related services. This public/private sector involvement in the scheme means the underlying ISO standards on which it is based must provide for a data format that allows both sectors to co-exist and be interoperable.

A final, critical element of a trusted network is the TEP. What is this? Well, it’s your smartphone, equipped with a code scanning application certified by a body such as the French Ministry of the Interior. Today, in France, the Otentik Code Reader is already being used to read about 50 official documents, including the French ID card, professional cards, and residency certificates.

Using a TEP application, the problem of not being able to trust the content of a code revealed by a smartphone camera, no longer exists.

Forcing people to download an application can be challenging. That’s why it is important to design a solution that allows all QR codes to be scanned with the standard reader on a smartphone, and not just with a dedicated application. However, using a trusted application provides protection against malicious QR codes.

It is worth noting that should this ISObased security standard be one day implemented across native iOS, Android, and other camera apps, it would allow for a seamless solution that reads non-VDS secured 2D codes while simultaneously enabling the scanning of all VDSprotected documents and objects, with automatic redirection to the corresponding legitimate websites.

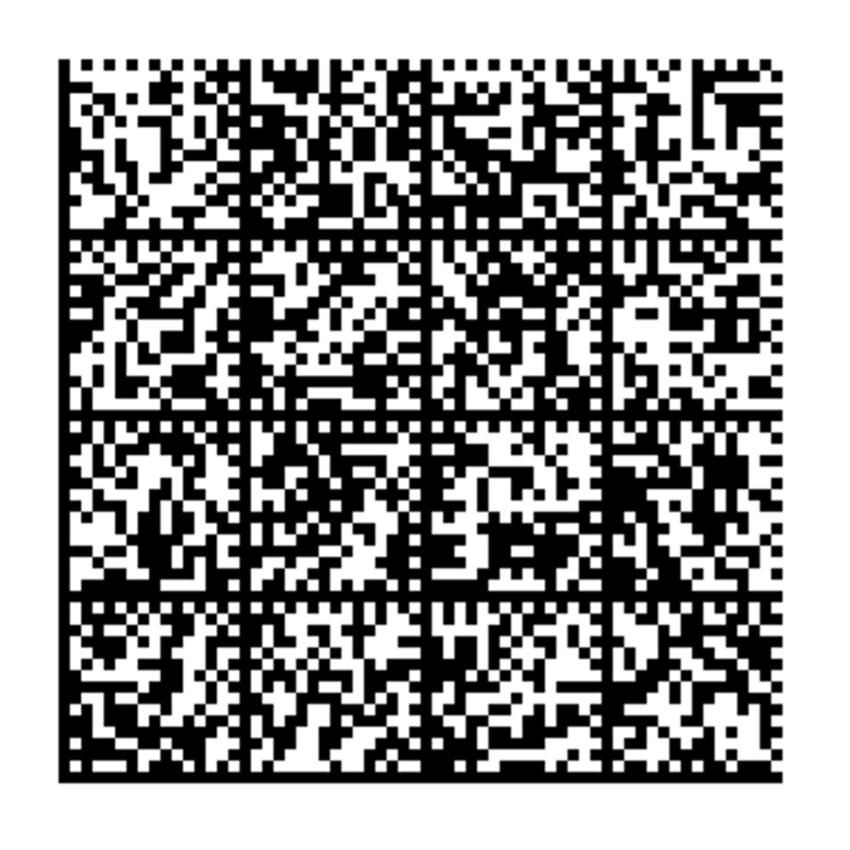

Test it yourself:

1. Download the Otentik Code Reader application from your preferred app store.

2. Scan the QR code below with your smartphone’s standard QR code reader. There is no protection; you could land on a malicious website that could lead to significant damage.

3. Now try again with the Otentik TEP application. The app verifies the encoded digital signature of the QR code. This time, you will enjoy a fully secure experience on a legitimate website.

Beyond France, another VDS scheme implemented via the Otentik network is in the Ivory Coast. This scheme provides an excellent, best-practice example of how the public and private sector joined forces to implement a global interoperability solution based on ISO standards. Official Ivory Coast documents can now be read and interpreted securely anywhere in the world, and, by the same token, all Otentik secure codes from other parts of the world can also be recognised.

VDS_Anti-Quishing_QRc

VDS_Certificat-CI_DMx – on Ivory Coast’s residence certificate, issued by the Office National de l’Etat Civil et de l’Identification

The principle is the same for tax stamps as for other documents. If a unique ID on a tax stamp integrates a VDS, we will have a code that, while secure, can be treated with the same reading application as a host of other official documents.

Although the most straightforward way of integrating a VDS into a tax stamp would be to physically add it as an entire dataset, the limited space available on the stamp means that other approaches may need to be used. One such approach would be to incorporate an electronic signature and VDS ‘header’ (containing information about the VDS) into a tax stamp’s existing barcode, which means the stamp would not need to carry a second, VDS code.

The VDS could also contain (or securely link to) information and guidance on the physical security features used on the tax stamp. This would, in particular, help customs and field inspectors to familiarise themselves with these features.

Over the next few years, we foresee discussions around the convergence of tax stamps with regulations such as those related to digital product passports (DPPs), as well as advanced discussions around direct-to-product marking.

Since the intention of the EU is for DPPs to be widely applied to most sectors, including tobacco products – which currently carry unique codes mandated under the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) – the tax stamp and traceability industry should keep a close eye on the direction taken by these various initiatives, in particular regarding the upcoming revision of the TPD.

1 - https://www.statista.com/statistics/1297768/us-smartphone-users-qr-scanner/